The Anatomy of a Witch Hunt: Modern Persecution Without Superstition

In the dark corners of history, witch hunts have long been associated with the frenzied persecution of those believed to possess maleficent supernatural powers. Yet, as we advance into the modern age, the phenomenon of witch hunts persists—stripped of its superstitious trappings, but alive in the form of political, social, and digital persecution. This article explores the anatomy of modern witch hunts, dissecting the patterns and motivations that drive society to scapegoat individuals or groups without the invocation of the supernatural.

Anatomy of a Modern Witch Hunt

Modern witch hunts unfold through a series of identifiable stages. While they lack the burning stakes or spectral evidence of the past, they are fueled by the same human tendencies toward fear, suspicion, and the desire for homogeneity. The phases of a contemporary witch hunt typically include:

- Identification: A trigger event, often a scandal or a crime, brings a person or group into the public eye. The identified party is frequently portrayed as a symbolic enemy, embodying broader societal anxieties.

- Amplification: Media institutions and social networks play a critical role in propagating the perceived threat. The virality and reach of online platforms can accelerate the spread of information—and misinformation—beyond control.

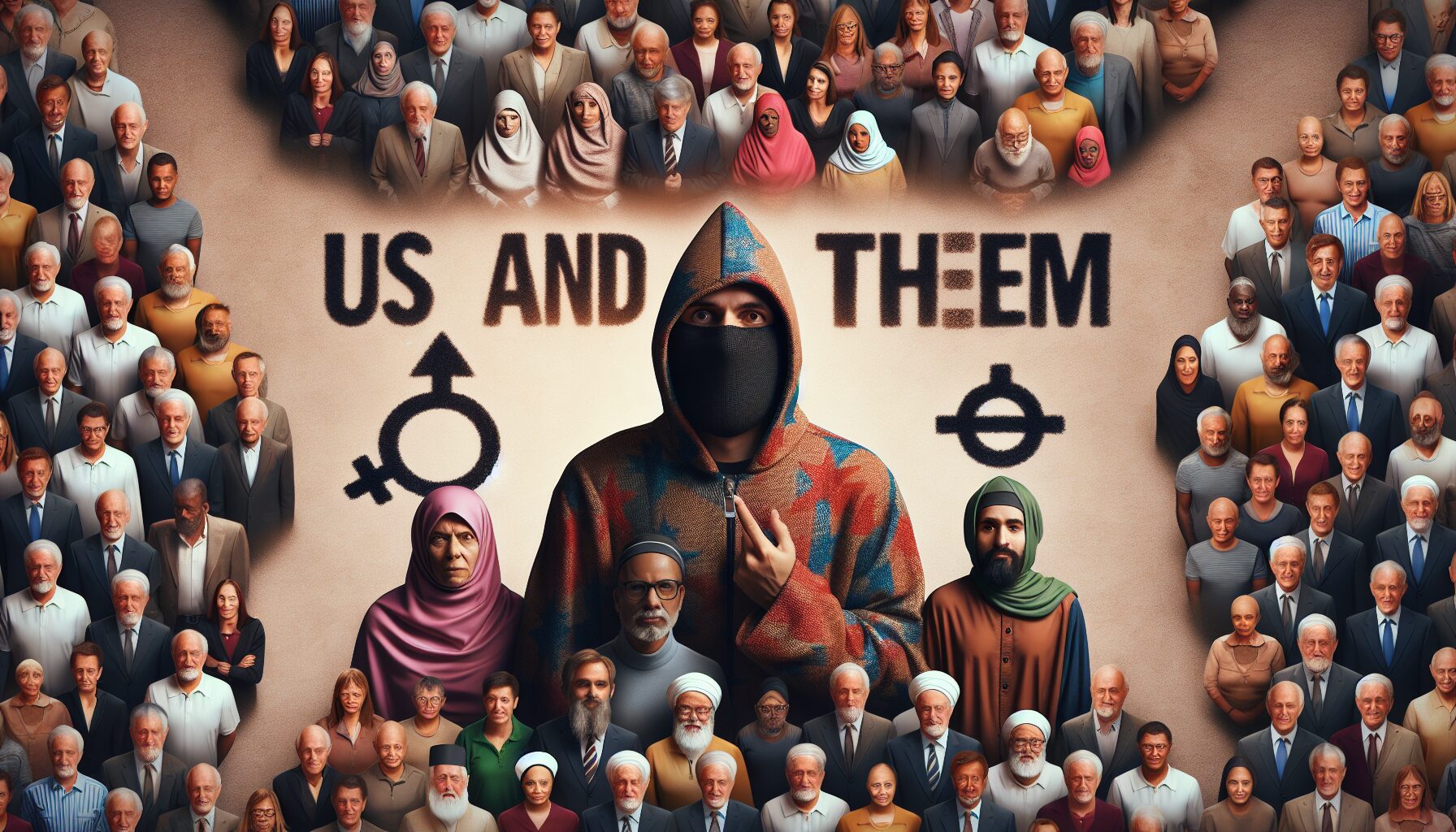

- Polarization: The issue becomes divisive, forcing individuals and communities to take sides. Norms of civil discourse break down as adversarial identities are reinforced.

- Condemnation: The targeted party is subjected to public shaming, ridicule, or penalty. This may include formalized condemnation by institutions or informal retribution by online communities.

- Resolution (or Persistence): The witch hunt either resolves with a formal conclusion, such as a court ruling or retraction, or continues indefinitely, affecting the lives of those targeted.

Historical Parallels and Patterns

“The witch-hunt is both the symbol and the practice of irrational aggression in times of stress.” – Arthur Miller, The Crucible

Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, though set in the Salem witch trials, offers timeless insight into how fear and suspicion can escalate into mass hysteria. This allegory of McCarthyism in 1950s America underlines a fundamental pattern: the exploitation of communal fears to target outliers as a means of reinforcing collective identity. Such patterns persist today in various forms.

The Role of Media

In the digital age, the media’s influence on modern witch hunts cannot be overstated. Viral social media campaigns and 24-hour news cycles have created an environment where information is rapidly disseminated, often without adequate verification. According to a Pew Research Center report, a significant portion of Americans obtains news through social media platforms, which not only amplify messages but also sometimes distort them through algorithms that prioritize engagement over accuracy.

The consequences of this media landscape manifest in immediate public reactions, ranging from hashtag campaigns to more severe outcomes, such as doxxing or SWATting. Media can both ignite witch hunts and serve as platforms for targets to plead their case, though the latter often comes too late or goes unnoticed amidst the noise.

Psychological Underpinnings

The psychology of witch hunts has its roots in human nature. The need for belonging, compounded by fear and anxiety, can lead individuals to conspire against perceived threats. Social psychologist Gustave Le Bon remarked on the susceptibility of crowds to irrational behavior in his work, “The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind,” noting that crowds unite under emotions rather than logic.

- Conformity: Individuals are prone to adopting the attitudes and actions of their social groups, particularly during crises.

- Projection: Society often projects its frustrations and insecurities onto a scapegoat, relieving collective stress through blame.

- In-group vs. Out-group Dynamics: There’s an inherent tendency to vilify those perceived as outsiders, particularly when social cohesion is threatened.

Consequences

The aftermath of a modern witch hunt can have profound effects on both the victims and society at large. For individuals, the impact ranges from loss of reputation and privacy to ongoing threats to personal safety. The damage to victims can be long-lasting, with consequences such as job loss, social isolation, and mental health issues.

On a societal level, witch hunts erode trust in institutions and media, sow division among communities, and stifle open dialogue. Trust in social and governmental institutions can decrease significantly, leading to a fragmented social fabric.

Moving Forward: Prevention and Mitigation

To prevent and mitigate modern-day witch hunts, society must foster environments where reasoned discourse and critical thinking prevail over mob mentality. This involves cultivating media literacy, promoting empathy, and encouraging dialogue across different social strata. Addressing the root causes of fear and division can also alleviate the underlying tensions that fuel witch hunts.

Organizations and individuals can take proactive steps by advocating for responsible journalism, fact-checking news stories, and holding social media platforms accountable for the content shared on their networks. Education systems can play a pivotal role by incorporating media literacy and critical thinking skills into curriculums, equipping future generations to navigate the complexities of information in the digital age.

In conclusion, while the trappings of witch hunts may have evolved, their essence remains rooted in shared human vulnerabilities. By understanding the anatomy of modern witch hunts, society can better recognize and counteract these episodes of collective persecution, ensuring that justice and reason prevail over fear and aggression.