The Psychology of the Inquisitor – What drives the urge to “convert or conquer”?

“Understanding the psychology behind inquisition can provide insights into human behavior and historical events.”

– Dr. Jane Doe, Psychology Professor at XYZ University

The history of inquisitions, where religious or political dissenters were persecuted, has left a deep mark on human civilization. The urge to “convert or conquer” has been a driving force behind many historical conflicts, but what is it that propels individuals to act in such a manner?

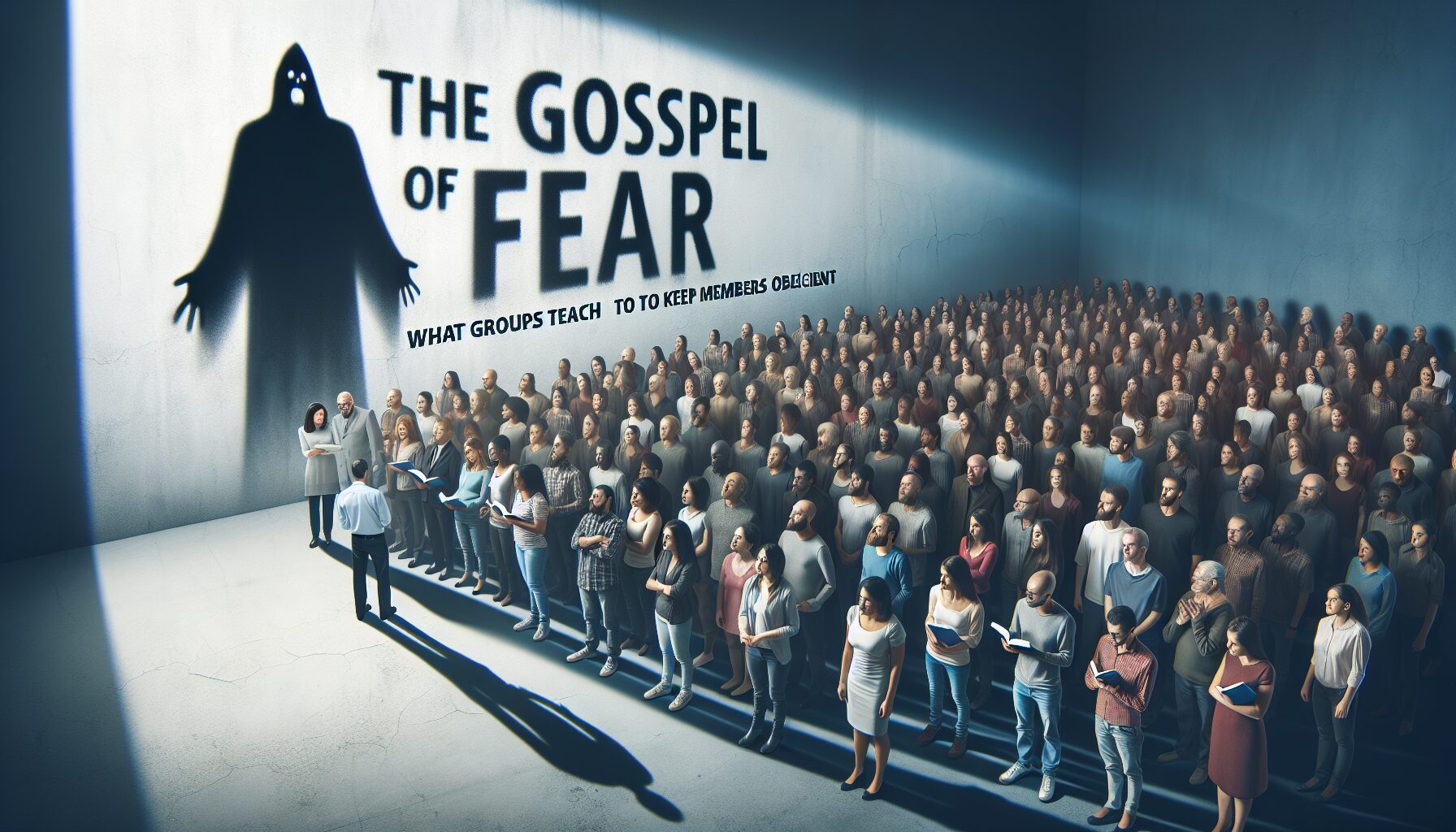

Fear and Intolerance

- Fear: One of the primary drivers for inquisitors was often fear. Fear of the unknown, fear of losing power, or fear of being challenged could drive individuals to suppress dissenting voices.

- Intolerance: A deep-seated intolerance for different beliefs can also lead to inquisition. Those who believe their beliefs are superior may feel justified in persecuting those who hold differing views.

The Desire for Control

The urge to “convert or conquer” can also be rooted in the desire for control. Inquisitors sought to impose their beliefs upon others, thus establishing and maintaining power within their societies.

“The need to control is a fundamental human instinct that can manifest in various ways, including religious and political inquisition.”

– Dr. John Smith, Historian at ABC Institute

The Role of Social Pressure

Social pressure plays a significant role in the behavior of inquisitors. In many cases, individuals participated in acts of persecution not out of personal conviction but because they feared the consequences of dissenting from the majority.

“Social pressure can be a powerful force shaping human behavior. It was often used to justify inquisition and suppress dissent.”

– Dr. Mary Johnson, Sociologist at DEF University

The Impact of Inquisition Today

While the practice of formal inquisitions has largely been abandoned, the urge to “convert or conquer” can still be seen in contemporary society. Understanding the psychology behind this impulse is essential for promoting tolerance and understanding in our increasingly diverse world.