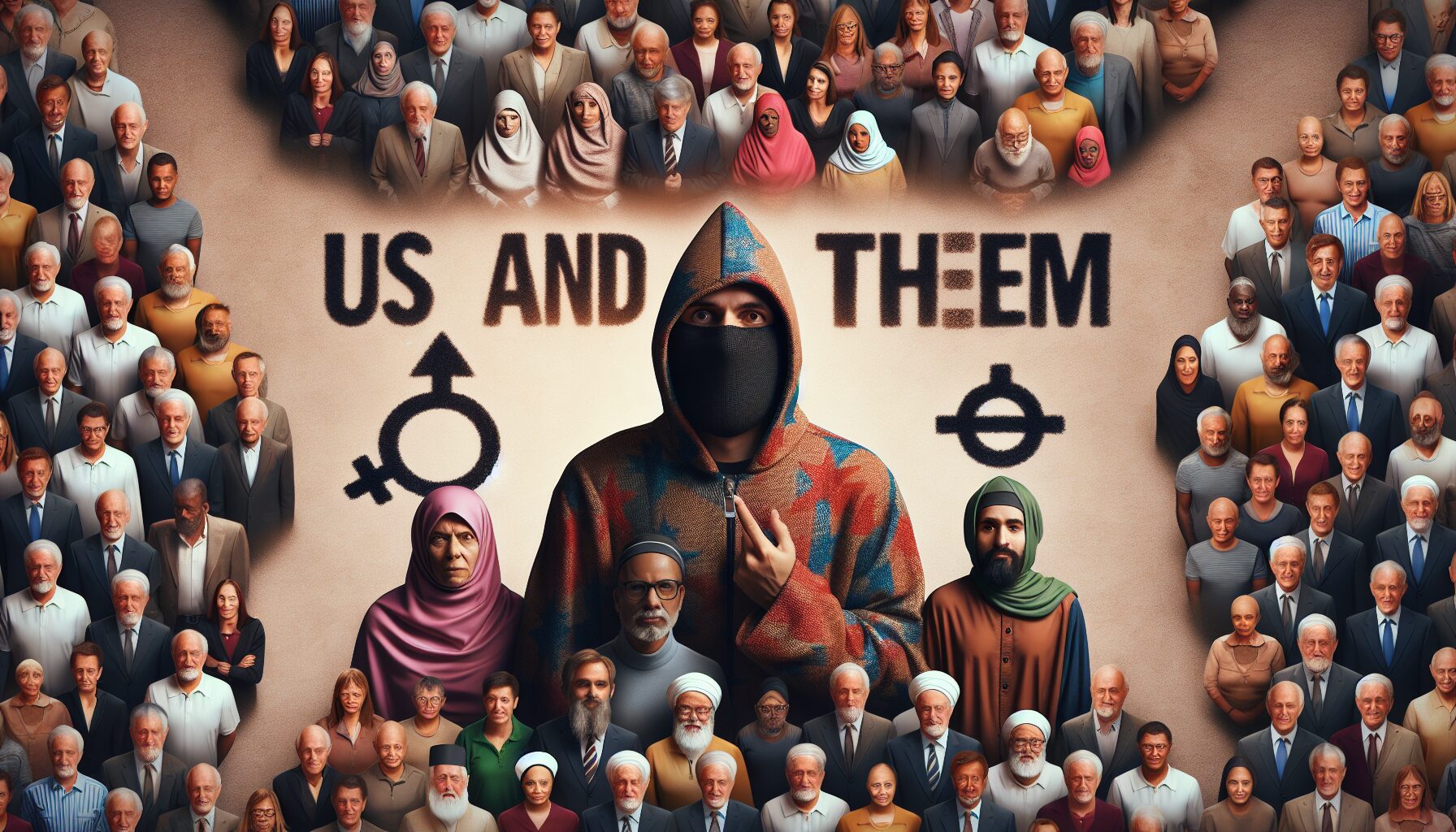

Us and Them: The Social Mechanics Behind Religious Scapegoating

Throughout history, societies have often resorted to scapegoating certain religious groups, a phenomenon that has both social and psychological roots. Understanding the mechanisms behind this behavior reveals much about how humans interact in complex social structures.

The Concept of Scapegoating

Scapegoating involves unfairly blaming a person or a group for problems they did not cause. This practice is often harnessed to deflect responsibility, unite communities against a common “enemy,” and reinforce social cohesion within the dominant group. The term originates from an ancient ritual described in the Bible, where a goat was symbolically burdened with the sins of the people and driven away into the wilderness.

Psychological Underpinnings

According to Dr. Robert Jones, CEO of PRRI (Public Religion Research Institute), “When societies experience upheaval, individuals look for a cause; religious minorities often become the convenient scapegoat.” The American Psychological Association notes that scapegoating fulfills psychological needs, such as the need for a clearly defined foe during times of fear and uncertainty.

The Mechanism of ‘Us vs. Them’

- Identity: Religion is a core part of identity for many, and any threat to that can provoke defensive and aggressive responses.

- Group Dynamics: Social Identity Theory suggests that people derive pride from their group membership. Distinguishing “us” from “them” reinforces group solidarity.

- Perceived Threat: Sociologist Ervin Staub explains that perceived threats—whether economic, social, or cultural—often catalyze scapegoating dynamics.

Historical Examples

The persecution of Jewish communities throughout history, particularly during the Black Death in medieval Europe, is a classic example of religious scapegoating.

“Jews were accused of poisoning wells and causing the plague, resulting in widespread violence and massacres,”

recounts the Yad Vashem Institute. This illustrates how myths and stereotypes are often fabricated or exaggerated to serve the scapegoating agenda.

The Cost of Scapegoating

While scapegoating serves as a temporary balm for societal fears and anxieties, it ultimately negates the principles of inclusivity and mutual respect. It also perpetuates cycles of violence and misunderstanding. Psychologist Gordon Allport warned that, “Continual discrimination against minority groups not only destructs humanity but corrodes the soul of the society that indulges in it.”

Studying the social mechanics of religious scapegoating compels us to question how we can prevent history from repeating itself. By fostering environments that emphasize empathy, understanding, and education, we can begin to dismantle the destructive mechanisms of “us” versus “them.”